Solutions in Search of a Problem: A Defense

“Solutions in search of a problem” are inventions with interesting properties that have no clear commercial use. They seem like they would be useful. But no one can figure out what for.

YCombinator says that pursuing solutions in search of a problem (SISPs) is the single most common mistake founders make when looking for ideas.

That might be right.

But it’s worth pointing out that many of the most important inventions of the last 100 years could justifiably be called SISPs. They began with the (often accidental) creation or discovery of something that had surprising properties and no obvious practical use.

For instance…

Transistors

Transistors were invented at Bell Labs in December of 1947 within a solid state research group that had no specific operating goal. There was no reason to suspect that solid state physics (a brand new field at the time) would yield anything useful for the telecommunication industry anytime soon. And yet, within 2 years John Bardeen and Walter Brattain had created the world’s first semiconductor device.

[Baum, their manager,] was immediately convinced that the [transistor] device was not only real but important. It was, he privately suspected, more than an amplifier, more than a switch, more than a replacement for the vacuum tube. But [. . .] knowing precisely what it portended or indeed how it all fit together would require some serious consideration as well as some time. (Idea Factory, Ch 12, 17:00 in the audiobook)

Importantly, no one at Bell Labs had digital computers in mind when they invented transistors. It took people outside of Bell Labs to point out that transistors could be used to create logical gates and switches (their most important use today).

“It appears that transistors might have important uses in electronic computer circuits”, J. Forrester, the Associate Director of MIT’s Electrical Engineering Department wrote to Baum in July of 1948. “In view of this fact, we would like to obtain some sample transistors when they become available in order to investigate their possible applications to high speed digital computing apparatus.” (Idea Factory, Ch 13, 16:20)

Today transistors are used in virtually all electronics. No one could have known how important they would turn out to be because they didn’t have digital computers in mind. But eventually the transistor found its purpose.

Airplanes

The Wright brothers filed their patent for a “Flying Machine” in 1903, at which point the contraption was widely regarded as a mere curiosity. Airplanes became literal circus attractions.

The practical value of airplanes had not yet matured by the start of the 1920s. In the absence of consistently viable commercial business or thriving passenger traffic, one of the few civilian functions of aviation was entertainment. (Realizing the Dream of Flight)

Airplanes are interesting toys, but of no military value.

– Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Allied Commander, WWI [Source]

This lasted until WWI when countries began experimenting with them for reconnaissance, and eventually actual warfare.

Machine Learning

In 1950, Claude Shannon built a mouse-like object that learned how to navigate through a maze. (Pictures here.) After it had been given a chance to explore an arbitrary maze, it could be placed in any spot and find its way out. It’s the first known instance of machine learning.

There was no obvious use for the technology at the time. Shannon built the mouse as a hobby project in his free time.

Lasers

Developed by several people and teams in the late 1950s (including one at Bell Labs). From Wikipedia:

When lasers were invented in 1960, they were called “a solution looking for a problem”. Since then, they have become ubiquitous, finding utility in thousands of highly varied applications in every section of modern society, including consumer electronics, information technology, science, medicine, industry, law enforcement, entertainment, and the military. [Source]

Velcro

Conceived by Swiss engineer George de Mestral after a hunting trip in 1941 when he looked at plant burs that were sticking to his clothing under a microscope. Also from Wikipedia:

De Mestral obtained patents in many countries right after inventing the fasteners, as he expected an immediate high demand. Owing partly to its cosmetic appearance, though, hook-and-loop’s integration into the textile industry took time. At the time, the fasteners looked as though they had been made from leftover bits of cheap fabric, and thus were not sewn into clothing or used widely when it debuted in the early 1960s. It was also regarded as impractical.

No one saw a use for it until NASA used it in the Gemini and Apollo programs, over 20 years after Velcro was initially developed:

[T]he fabric got its first break when it was used in the aerospace industry to help astronauts maneuver in and out of bulky space suits. However, this use reinforced the view among the populace that hook-and-loop was something with very limited utilitarian uses. The next major use hook-and-loop saw was with skiers, who saw the similarities between their outerwear and that of the astronauts, and thus saw the advantages of a suit that was easier to don and doff. Scuba and marine gear followed soon after. Having seen astronauts storing food pouches on walls, children’s clothing makers came on board.

Today, it is hard to imagine having a child without the use of Velcro. But this was never on de Mestral’s mind.

The Internet

Okay, okay, it’s a bit of a stretch to call the Internet a SISP. But it is a good example of a technology developed for one thing that actually ended up being useful for another.

The initial purpose for creating a large network of computers was actually time-sharing – splitting up processing power among many different users of the same machine. It was J.C.R. Licklider’s famous 1963 memo on the challenges of time-sharing that articulated a greater vision for the technology and led to ARPANET, the precursor for the internet.

But almost all of the specific things that we use the internet for today, and which give it consumer value, were not in the minds of the people who created it, as is obvious when you read Licklider’s memo. No one was pitching an invention to help us order food, find dates, get rides, rent houses, share cat videos, and watch other people play video games. These are uses for it we discovered much later.

ChatGPT

No apologies for this one. ChatGPT was clearly a solution in search of a problem – albeit one that found it’s problem incredibly quickly.

OpenAI had developed ChatGPT months before they released it. They seem to have sat on it because most people at the company thought the product wasn’t useful. Beta testers didn’t even know what to do with it.

None of us were that enamored by [ChatGPT] [. . .] None of us were like, ‘This is really useful.’ – Greg Brockman, cofounder of OpenAI [Source]

“I will admit, to my slight embarrassment … when we made ChatGPT, I didn’t know if it was any good,” said [Ilya] Sutskever. “When you asked it a factual question, it gave you a wrong answer. I thought it was going to be so unimpressive that people would say, ‘Why are you doing this? This is so boring!’” he added. [Source]

Brockman said the decision to release the chatbot was a last resort after a string of internal issues, such as beta testers not knowing what to ask the bot, and a failed attempt to create expert chatbots. [Source]

The chatbot’s instant virality caught OpenAI off guard, its execs insist. “This was definitely surprising,” Mira Murati, OpenAI’s chief technology officer. [Source]

Apparently Sam Altman didn’t even tell OpenAI’s board before ChatGPT was released. The most obvious explanation is that he had no idea how useful people were going to find it.

The essence of a SISP is that an inventor thinks his/her creation is interesting but doesn’t know what concrete problem it solves. I think ChatGPT checks both of these boxes.

Clearly OpenAI thought it was interesting – they used internal resources to develop and test it over the course of several months. Equally clearly, however, they did not know what problems ChatGPT would solve. They didn’t think people would find it useful at all. They thought people wouldn’t know what to do with it. They thought people would be bored.

Time to Problem

ChatGPT is an example of a SISP that found its problem very quickly. Said another way: its time to problem was very low. The same cannot be said for the other products on this list.

Transistors took about 5 years to be commercially viable. Their first economically successful use was the Sonotone 1010, a hearing aid (not a computer). Airplanes took 7 years: the first commercial flight was in 1914. If we peg the creation of the internet to the launch of ARPANET in 1969, then it wasn’t commercially viable for 21 years, when email clients like Pegasus Mail became available. Machine learning took a staggering 39 years to catch on, eventually doing so at financial institutions with the development of FICO scores.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of many of these inventions. Transistors, airplanes, lasers, the internet, etc, all have fundamentally changed the world. They’re on the top of just about everyone’s list of the most important inventions of the 20th century. They created (and continue to create) trillions of dollars in economic value on an annual basis.

Yet, it’s also hard to dispute YC’s claim that pursuing these kinds of things is a mistake. It’s impossible to build a business around a product that’s going to take 40 years to catch on. The internet didn’t make its creators rich. Nor did the transistor. It’s not even clear that ChatGPT will.

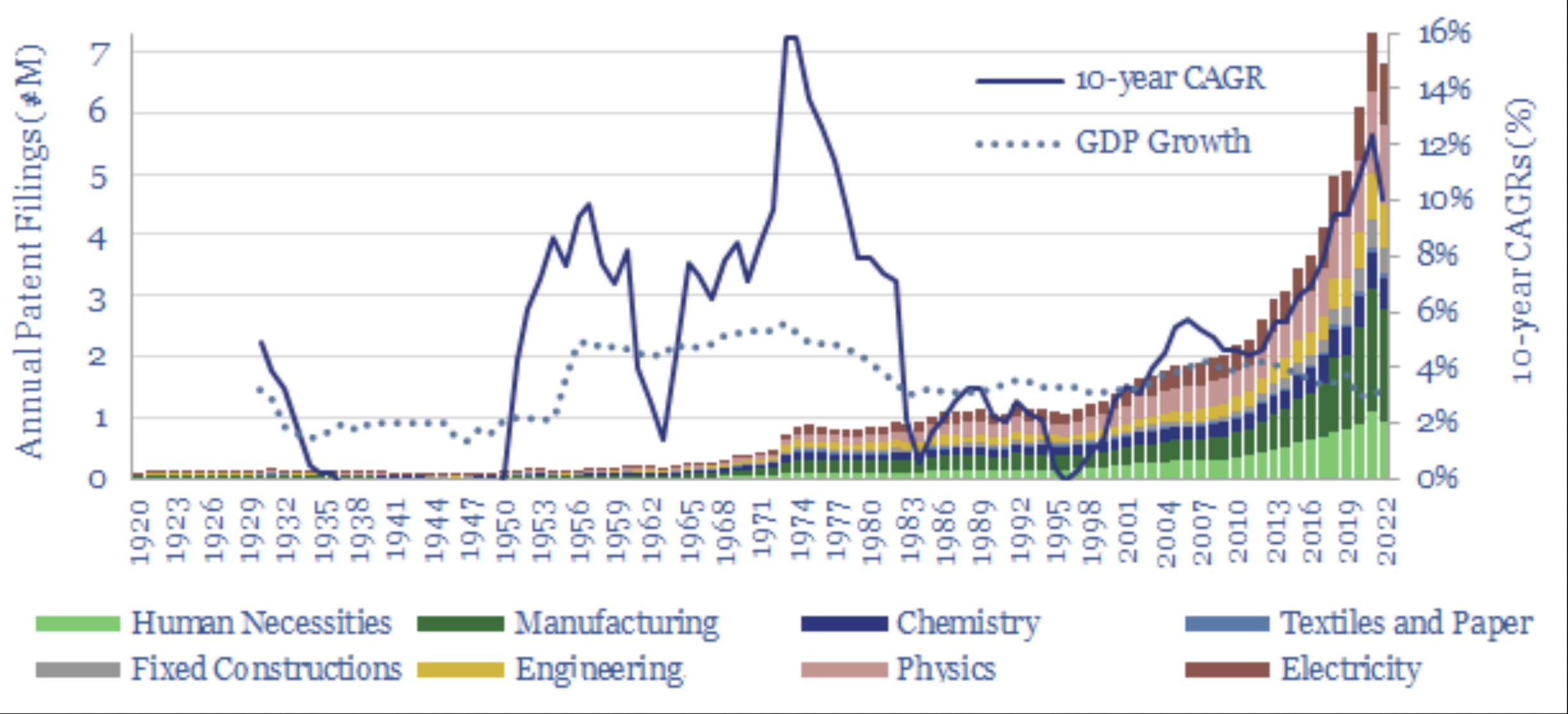

But, as ChatGPT demonstrates so well, technology advances much faster now than it did at the time of these other inventions (early/mid 1900s). This is evident in the increase in patent filings over time.

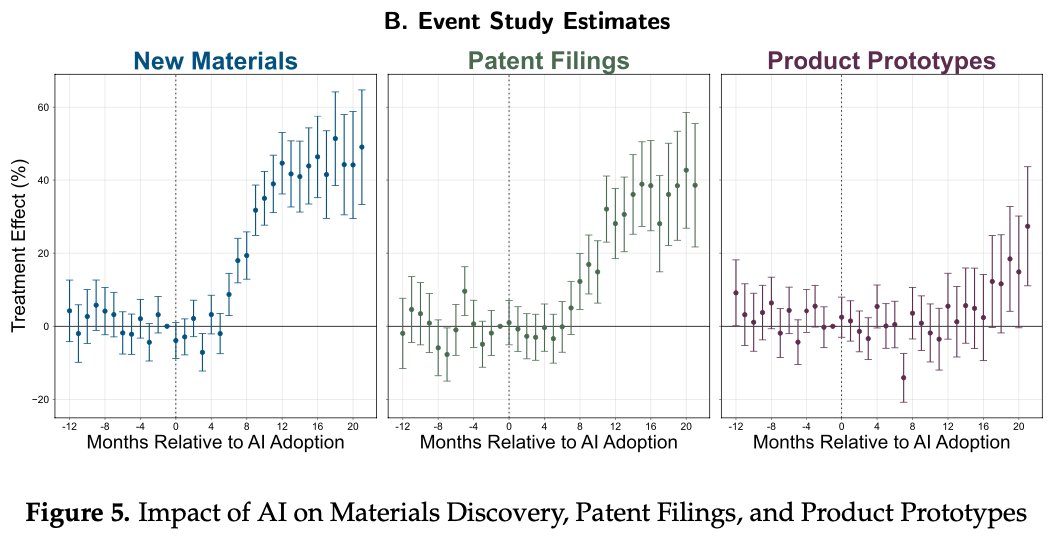

This trend is being further exaggerated by AI. This is from a recent paper that looked at the economic effects of AI-assisted materials research at a large R&D lab. It found that:

AI-assisted researchers discover 44% more materials, resulting in a 39% increase in patent filings and a 17% rise in downstream product innovation.

The chart version of this is dramatic:

(From “Artificial Intelligence, Scientific Discovery, and Product Innovation” by Aidan Toner-Rodgers.)

With new technology comes new problems to solve. The invention of the transistor created lots of new problems even as it solved old ones:

- how to create extremely pure semiconductor crystals

- how to manufacture them at scale

- how to find more common elements (than Germanium) to build them with

- how to precisely introduce impurities into the crystals

- how to dissipate heat when lots of transistors were being used in close proximity

The point is: the explosion of inventions has effectively sped up time. The time it will take for us to see n new technical problems is a fraction of the time it would have taken to see n problems emerge 100 years ago.

This means that if you do create something fundamentally useful, the amount of time it will take for you to find a problem for it to solve (and thus monetize it) is likely a fraction of the time it would have taken 50-100 years ago. That’s also ignoring the fact that it’s much easier to discover problems now than it ever has been before (thanks to the internet). Time-to-problem is just going way down.

So, will you be able to monetize an invention before you run out of money? The answer isn’t definitely “no”. As AI continues to permeate society and increase creativity, and the internet continues to facilitate problem discovery, there is going to be intense downward pressure on time-to-problem. At some point, maybe soon, the risk/reward profile will invert.

Conclusion

There’s a lot worse things that you could be doing with your time than inventing things. A bunch of impractical inventions changed our world for the better, despite being SISPs, and despite not making their creators rich. And the odds of finding a problem an invention can solve have never been better.