Your medical records are the most important thing missing from your will

DISCLAIMER: I am neither a doctor nor a lawyer and this does not constitute medical or legal advice.

I am leaving my medical records to my children and grandchildren in my will. I wish my grandparents had done this for me. I hope my parents will consider doing it. You should consider doing it too.

My grandparents weren’t alone in omitting their medical records. Almost everyone does. A friend who practices estate law told me that his partner, who has been writing wills for 30 years, has only had medical records come up once. And only then because the children in the family didn’t talk and the father needed to make sure all of the kids were informed of a consequential medical condition he had.

There is a very real possibility that your medical records will materially benefit your children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Depending on the situation, they could even save their lives. This can be the case even if you don’t currently have any obvious medical condition.

An example from my own life might help to make this concrete.

I recently found out that I have very high (99th percentile) levels of Lp(a). This blood test is infrequently ordered but pretty important. And my results were not good. As the CDC optimistically puts it:

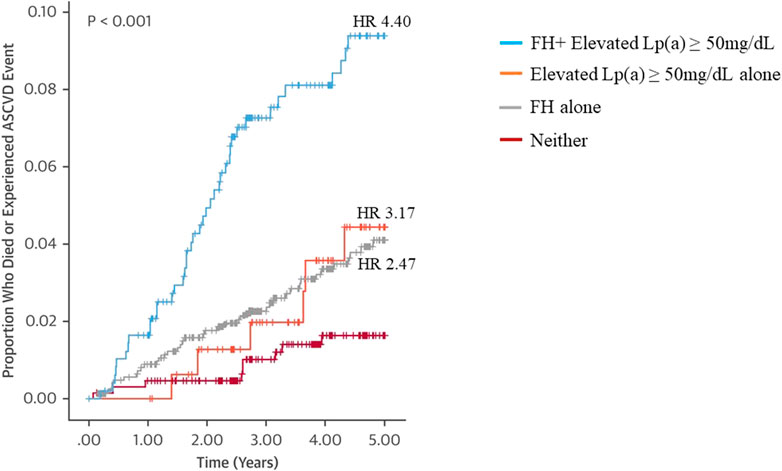

High levels of lipoprotein (a) increase your likelihood of having a heart attack, a stroke, and aortic stenosis, especially if you have familial hypercholesterolemia or signs of coronary heart disease.

Familial hypercholesterolemia is a genetic disorder that causes chronic high LDL cholesterol. And having it in addition to high Lp(a) increases the risk of dying of cardiovascular disease by a further ~40% over high Lp(a) alone. [0] Because the genetics are complicated, the CDC says:

the first step is to collect your family health history of heart disease and share this information with your doctor.

Unfortunately, I don’t really know whether my family members had heart disease or high cholesterol. At best I have anecdotes and gossip that are two generations removed from the source. Memory being what it is, these anecdotes have to be taken with a huge grain of salt.

I don’t blame anyone for this. In truth, my grandparents would have never thought that anyone would benefit from knowing their cholesterol numbers. (They probably doubted that they’d benefit from knowing them.) They didn’t know anything about Lp(a). Almost no one did. Researchers didn’t start putting things together until the early 1980s. Even now most people don’t know about it.

My point is: we are in the same epistemic position today that my grandparents were in decades ago.

Medicine will continue to advance. New diseases will continue to be discovered. And medical records that today seem inconsequential will turn out to be early warning signs of significant conditions we’ll only identify decades from now. You can’t know whether your medical records will matter to your descendants until they do.

When it comes to collecting your own medical records, the process is simple. You just have to call the provider, ask for the records, and (sometimes) authenticate who you are by answering a few questions. Then they’ll send you the records they have. HIPAA law requires them to do this, so they won’t resist.

They’ll even send your records if they contain evidence of malpractice. A close family member once requested the records from her surgery and upon receiving them learned that a sponge had been left inside her. I’ve never had a problem getting copies of my records – provided they still exist (more on this below).

While it’s easy to obtain your own records, it is very difficult to obtain the records of a deceased relative. HIPAA bars health care providers from disclosing information of deceased people for 50 years following their deaths except to the executor of their estate.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule protects the individually identifiable health information about a decedent [i.e. dead person] for 50 years following the date of death of the individual. [. . .] During the 50-year period of protection, the personal representative of the decedent (i.e., the person under applicable law with authority to act on behalf of the decedent or the decedent’s estate) has the ability to exercise the rights under the Privacy Rule with regard to the decedent’s health information, such as authorizing certain uses and disclosures of, and gaining access to, the information. [Source]

If you want to get the information, you need to determine the legal representative of each dead relative, then (if the representative isn’t also dead) have them request the information for you. If they’re also dead (not uncommon!) then get in touch with a lawyer. Because a new personal representative will need to be appointed by a probate court.

If you eventually secure the legal authority to obtain the records, you still need to find them. Which means tracking down each of the (often many) health care providers that your relatives saw. There is no master list for this. Which means again relying on anecdotes and doing a lot of leg work to call offices and confirm. And the providers might not even still be in business.

At this point you might be thinking: I don’t even know where all of my records are. Most people don’t! Heck, I don’t. This fact underscores not only the difficulty in obtaining other people’s records, but in actually passing your records on once you’re committed to it. I’ve been intentionally accumulating my records for the last ~8 years and I don’t have them all.

To make matters worse, providers are legally allowed to destroy records after keeping them for just 7 years. A couple months ago I called a provider to request records from a surgery I had in 2009. All they had left were the accounting records. So even after you’ve gotten access and found the providers, the records might not even still exist. In this way, HIPAA’s 50 year moratorium all but ensures that no one will ever see your records unless you pass them on.

In summary: it’s a process to obtain your family medical history. One that all but the most committed and well-financed won’t get through. But one which you can largely circumvent for your descendants by leaving your medical records to them as an explicit part of your will.

Footnotes

[0] See figure 1 in this study. The hazard ratio of high Lp(a) + FH is ~40% higher than the hazard ratio of high Lp(a) alone.